Possible World I: environment

Create a possible world

By drawing a slightly different image in front of each eye, the image can be made three-dimensional. By changing the image seventy-two times a second, it can be made to move. By drawing the moving three-dimensional image at a resolution of 2K pixels on a side, it can be as sharp as the eye can perceive, and by pumping stereo digital sound through the little earphones, the moving 3-D picture can have a perfectly realistic soundtrack.

So Hiro’s not actually here at all. He’s in a computer-generated universe that his computer is drawing onto his goggles and pumping into his earphones. In the lingo, this imaginary place is known as the Metaverse. Hiro spends a lot of time in the Metaverse …

— Neal Stephenson, Snow Crash

The goal of the Possible World project is to produce a one-minute narrative in which a simple entity interacts with a simple environment in a meaningful, complex way.

As defined by the hierarchy and types of modeling in parallelUniverses, an Environment involves greater conceptual complexity than the Element model you made in the last project, although this does not necessarily correlate to greater complexity in modeling geometry. Rather, it brings the modeler deeper into Composition and Material modeling. An Entity carries one into the fullest conceptual territory for modeling. It adds Kinematics through techniques of timeline manipulation, time-based deformations, and rigging — the “skeleton” and “muscles” — of the entity. This author avoids the term character as a conceptually limiting framework. While a character can be an entity, an entity is not necessarily a character.

Like an actor and a movie set, there is a strong linkage between environment and entity, which is why a significant portion of our term is devoted to the creation of this final project.

A possible world in two parts

However, the skills developed in the environment and the entity aspects of the project are discrete and complex. Thus, for evaluation, we divide the Possible World project into two parts:

- Possible World 01: Environment

- Possible World 02: Entity

We will describe the objectives and criteria for Possible World I below. A more detailed description of Possible World II will be saved for the next title. With that said, we still need to develop a framework for the unified work as a whole. We do that by creating several documents found in most animation projects. These include concept art, storyboards, shot designs, and a production chart. To keep them organized, we’ll post them to the blog in the virtual production folder you set up in the Production Folder exercise.

Representation or invention?

A generation ago, when an artist or designer approached environment modeling, it was seen as a surrogate for reality. An accurate representation of that reality was the standard criteria. In the past 30 years, with experiences ranging from Second Life to massively multiplayer online gaming, virtual reality to augmented reality, and the blurring of the boundaries between virtual and actual, the conceptual constraints and expectations for environment modeling have radically transformed.

Today, we can conceive of an environmental model, not purely as a representation, of something that historically exists or something from a possible future. We can also create an invention — an actual destination, not unlike the Metaverse described in Snow Crash. Gamers occupy invented environments on a fairly regular basis, though they are still prevented from experiencing Hiro’s total immersion by the looking-glass plane of the screen.

In any event, these polarities can manifest themselves whenever you create a new environment, react to an existing environment, or create tension between creation and reaction through juxtaposition. This project will engage you in one of these possible worlds.

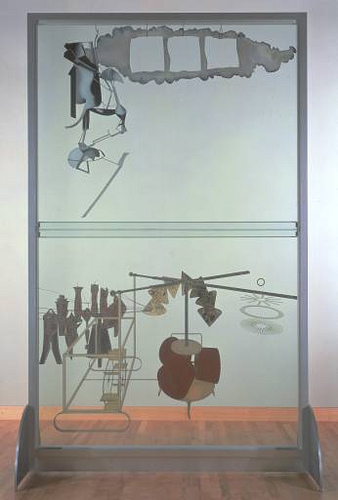

A case study: the Large Glass as representation…

Duchamp’s Large Glass has a long and storied history. It has influenced much of the direction of artmaking since being “definitively unfinished” by its author a century ago. Duchamp may not have known at the time that “definitively unfinished” meant that several artists would take up his mechano-erotic tragicomedy as source material for their own expression. But he lived to see his cheeky phrase evolve into work by other artists.

Richard Hamilton, the British Pop artist, approached Duchamp with an odd idea. The original copy of the Glass being too fragile to move, he proposed a replica — a representative model — to be created and placed in the Tate Museum. Believing as he did that idea transcends expression, Duchamp was delighted with the concept and gave his approval. Hamilton used the notes from Duchamp’s Green Box rather than photographs, like building a model from a blueprint. Hamilton’s dual, seen below, does not include the shatter in Duchamp’s, but a representation of the original conception.

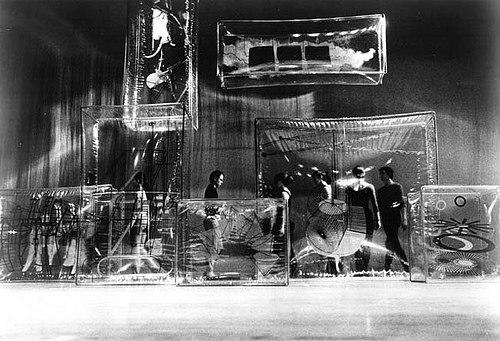

… and as invention

Jasper Johns was inspired by the Glass as well, though in a very different way. He used it as inspiration to invent an inflatable set for Merce Cunningham’s Walkaround Time in 1968, seen below. As Cunningham recounts:

We were having at dinner at the Duchamps’. … Jasper had the idea of making a set using elements of The Large Glass and he went over and asked Marcel. Marcel said, ‘Yes, but who would do all the work?’ Jasper said, ‘I would,’ so Marcel said that would be fine. … The inflatables took a long time to make, but two days before the premiere, Jasper told me he was going to do them again. He had to make them wider or they would fall over. The stage where we going to play was small, and I had to figure out if there would be space left for the dancers. … Marcel was at the premiere. He was 79 or 80, and he came up on stage afterwards. Jasper refused to bow – he never would – and as Marcel passed him he said, ‘Jasper, I’m just as afraid as you are.’ … In the end, we had to stop doing the piece because the set was being harmed. It’s at the Walker Arts Centre [sic] now. I’m glad people can see it because it’s so beautiful.

Merce Cunningham

The inflatable pillows remix the “characters” of the Glass to create an invented model. This is an entirely new environment, one where dancers can interact with the set. Although it is now a more static installation at the Walker Art Center, the work remains a very Johnsian take on the iconography of Duchamp.

The lesson: you can be inspired by something that exists to reproduce it, or remix it!

Creation or reaction?

When installation artists work, they often react to an existing environment in a site-specific or site-sensitive way, but they can also create an entirely autonomous thing. There is a curious interplay between the intellectual forces of drawing meaning from within existing conditions versus superimposing meaning from without. These artists will challenge you to think about modeling and environments from these perspectives, starting with Olafur Eliasson discussing the core issue of space:

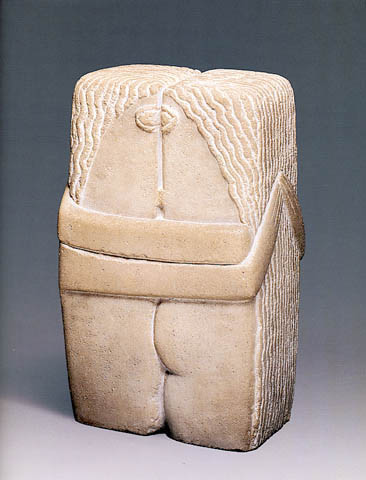

An echo of Eliasson’s final sentiment about the nature of the environment as a model is found in Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen’s playful but serious re-scaling of common objects. What do you get when you cross Philadelphia City Hall Tower with the different versions of Brancusi’s Kiss (one of which is at the Philadelphia Museum of Art)? The world’s largest clothespin, of course. But how is Clothespin NOT the same as a clothespin?

Building the unbuilt

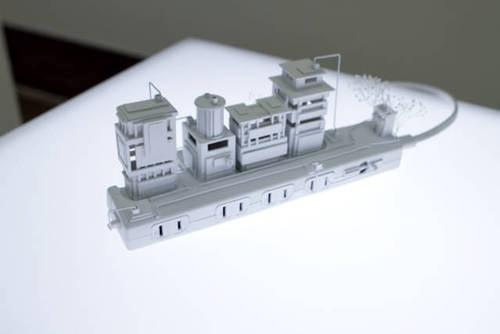

Another tower, Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International of 1920, was never built. The ultimate expression of the spirit of Russian Constructivism, its spirals and angles are echoed in much of today’s contemporary architecture. But Tatlin’s structure has only ever existed as a model. A room-sized analog model was used to propagate the design. But it was small in comparison to the ambition of a structure intended to dwarf the Eiffel Tower, the tallest building at the time.

The digital version seen below has more recently been created by Takehiko Nagakura. He is an Associate Professor of Design and Computation at MIT and spearheads the Unbuilt Monuments project there.

Scale-shifting

The Art Guys complete our trio of towers with Bonded Activity #55 (Skyscraper), part of the exhibition Leaded at the Palmer Museum of Art at Penn State University. They utterly transform the scale of the common pencil. At the same time, the tower feels decidedly model-ish—a tension of scale.

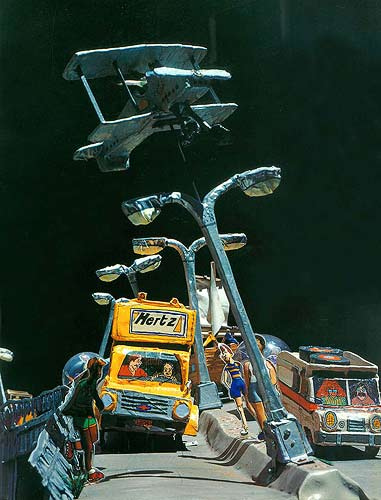

From making something small big to making something big small: enter Red Grooms. He may have heard echoes of the word ruckus in const-ruc-tion, inspiring his portrait of the city he loves as a not-far-off-the-mark hyper-cartoonish world. Manhattan in miniature still takes up a grand amount of space! We only see a tiny detail above, in one of the first installations enabled by CreativeTime.

Ruckus Construction Company’s installations were among the first immersive sculptural environments known as installation art. Other artists enjoy immersing their models in the mundane environment as we know it. They sometimes do it in guerrilla street art fashion, often with surreal results, as exemplified below.

Concept

Develop your concept. You can include, but are not limited to:

- Research. Discuss your own unique research requirements, one-on-one with your instructor.

- Conceptual development. A mix of hand sketching, physical model-building, and digital work might characterize this stage. Again, each option presents a unique developmental arc. Some, but not all, projects will need orthogonal reference drawings to import. If you’re comfortable with Illustrator or a CAD program, you can create reference drawings. However, this can sometimes add too much to the workflow.

- Found or made assets. Find or create image maps that can help you construct a world. Equirectangular projection images can create a realistic sky. Panoramic images can create a horizon. Seamless tile maps can develop a convincing material culture.

Place appropriate material (concept art can include image maps, for example) in the Production Folder post. Keeping a list of links for found materials here is helpful. If, for example, you are looking to create a grass surface, don’t limit yourself to the first seamless tiling material you find. Keep a list of links to a variety of these maps from which you can choose later.

Finally, articulate your concept in the first part of a post in your process journal or blog documenting this project.

Iteration

The iteration phase of this project is characterized by modeling activity.

- Modeling. In Maya, you will model the environment and its materials, textures, lighting, and movement of a camera through space. Remember the different kinds of modeling (Volumes and Surfaces, Composition, Material, Light, and POV) emphasized in this project, as discussed in parallelUniverses. Generally, you should think of your project as a virtual movie set — it is easy to over-model and lose time.

- In animation, the depth of modeling detail is quite different than it is in photo-real still rendering: avoid micro-beveling unless the camera tracks quite close to an object’s edge.

- Remember the new tools you have: a good bump or displacement map is worth a thousand polygons. Use your storyboard and shot designs to determine where the camera will point and model only those things that enter the mise-en-scene. Depending on the complexity of your project, you may need to develop props in scenes and reference them in a master scene.

- Time-Savers (maybe). It sometimes makes little sense to develop a model from scratch if something is available for you to appropriate. But beware:

- Many models come with licensing restrictions on permitted use. It is sometimes but not always easier to make exactly what you want instead of finding it.

- Different styles of modeling can look cobbled together: a cartoon chair in a realistic room can be jarring (or interesting).

- You can often find incompatibilities in the complexity of model geometry: keep to low-poly files if in doubt.

Asset sites

- If you can avoid these pitfalls it makes sense to peruse asset sites, just a few of which include:

- 3D Total has many free objects in .3ds and .mb formats.

- TurboSquid, the largest library of models on the web, has free objects in .3ds, .obj,.mb formats.

- Great Buildings… want the Eiffel Tower? Download it or hundreds of others in .3dmf format.

- Trimble 3D Warehouse has many of the same (and more) building models that can be downloaded as a .skp (SketchUp) file. From SketchUp (a free download) you can export to .dae format and then bring it into Meshlab (see below) for conversion into Maya.

- Hongkiat has published a post with many of these sites and about 50+ others.

- Meshwork (with Quesa installed in System>Library>CFM Support) for Mac will convert .3dmf files to .3ds, which can be taken to MeshLab…

- Note: This is the Library folder located at the root level (under the System folder), not the Library in your Users folder. You will not be able to do this on a networked machine in the lab, but you can do it on a personal laptop.

- MeshLab is an open-source freeware that can convert many files—.3ds, .stl, and others not compatible with Maya—into a Maya-readable .obj file.

- Meshmixer is free software that does the same: download it from the link.

- For props, furniture, and small objects, turn to Thingiverse but be careful: the models are crowd-sourced and quality is a mixed bag.

Again, keep a list of your explorations for assets in the Production Folder post for reference.

In your project post, describe your iterations.

Synthesis

Of course, we know that you integrate this project with the next one. But for demonstration of synthesis within this project, consider embedding any of the following in the final portion of your project post:

- Still image renderings at high-definition resolution (1920 X 1080).

- Renderings of props or referenced objects.

- Screen captures in the software, which might reveal structural decisions.

- A playblast that might quickly illustrate camera motion.