CHAPTER 1 — The History of Modeling

9-minute read

Prehistoric models and the cosmos

The first models attempted to create order out of randomness. Early hunter-gatherer humans must have felt the need to generate order in the relatively uncontrollable environment in which they lived. Among the most prevalent were models based on the pattern of celestial phenomena. Daily sunrise through monthly moon phases to the yearly return of seasons created a temporal order. The cycling stars, and our hard-wired proclivity to discover patterns, led to a system of charting that included constellations that survive to this day. Many of the texts associated with these ancient activities border on the pseudo-scientific and must be read critically. However, one can certainly find researchers working with intellectual, un-sentimentalized rigor.

The caves at Lascaux

Historically, scholars believed that celestial mapping and prediction was a habit of necessity formed out of the beginnings of agriculture. It was needed to foresee seasons of planting and harvest. However, independent archaeo-astronomer Chantal Jègues-Wolkiewiez has hypothesized that at least some chambers at the famous Neolithic cave painting complex in Lascaux, France turn out to be prehistoric models of the sky. The adjacent video illustrates her theory. These hunter-gatherers had no pragmatic agricultural need for modeling celestial cycles. Instead, they conflate the random star patterns with animals in their environment, creating one of the earliest tangible instances of model-making: the first constellations. 1

National Geographic, Stone Age Zodiac, 2009.

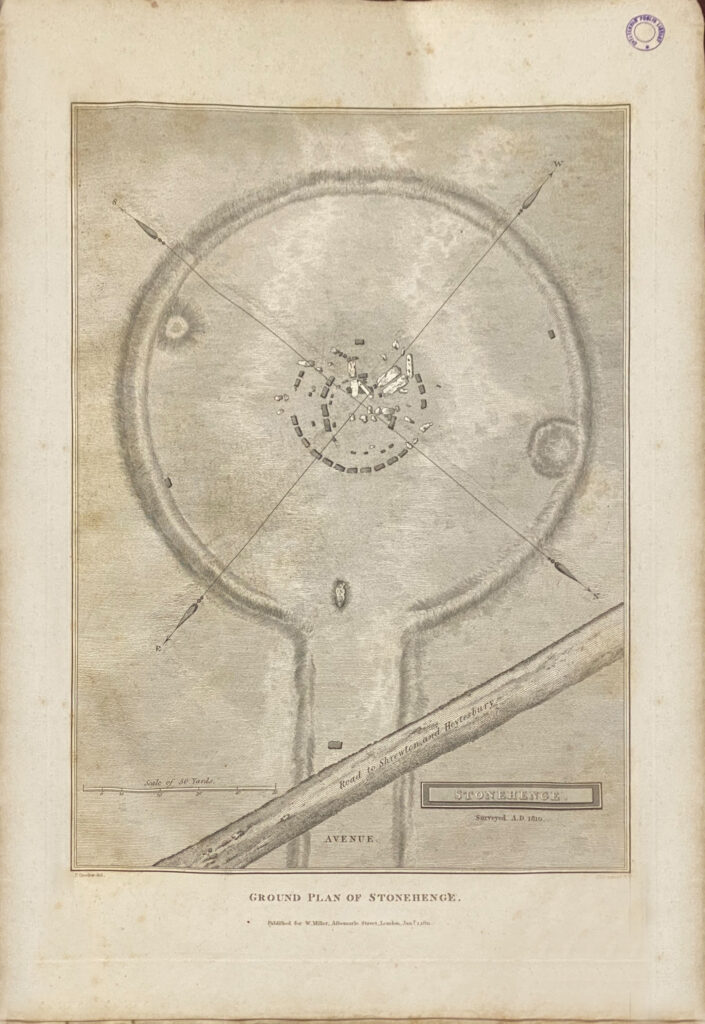

Stonehenge

Whether erected for agricultural, social, or religious reasons, the full purpose of the monument at Stonehenge may never be understood. At a minimum, its function as a cosmic apparatus is clear, as the structure marks many astronomical phenomena, the most celebrated of which are the solstices. Particular slits between standing stones reveal several other significant celestial events as well. However, not every slit functions this way, and we can demonstrate that a few simple markers would perform the same essential function. So why create the seemingly superfluous standing stones and multiple concentric rings comprised of stones and barrows?

At the very minimum, they create a special, and some would say sacred, territory. They may suggest more: a cosmological model referencing man’s place in the natural schema. The center reference point, from which so many celestial phenomena can be witnessed, suggests these humans regard themselves as occupying a central place within the cosmic order. The concentric circles seen here can be seen functioning both as a precise astronomical machine and as a metaphor, a model of our position within the cycles of nature and the cosmos. 2

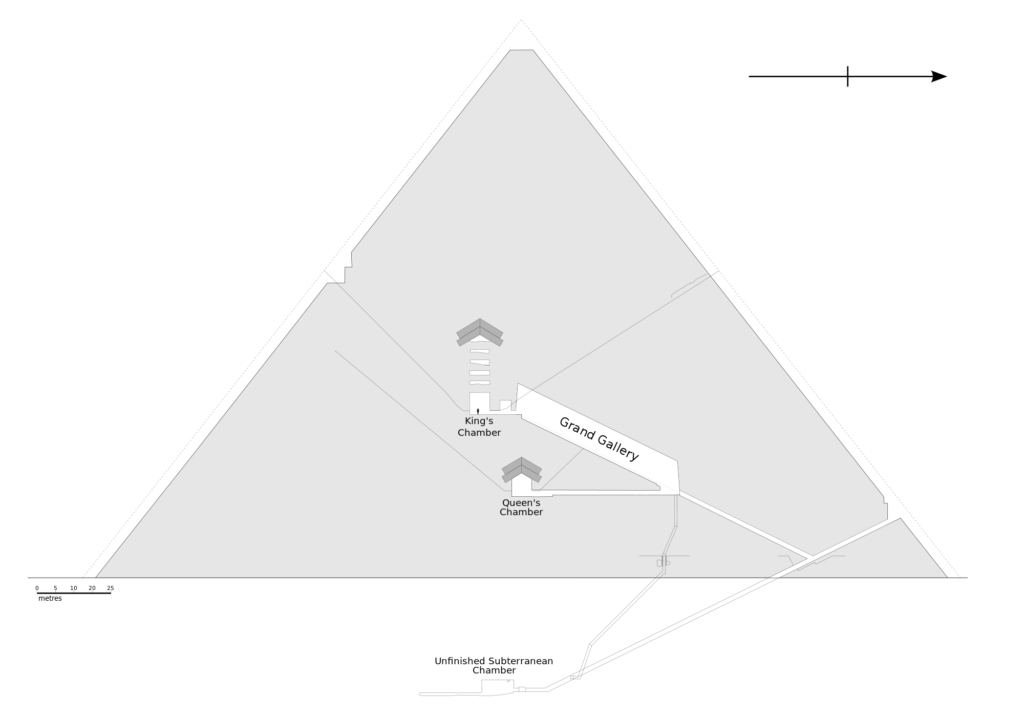

The Great Pyramid at Giza

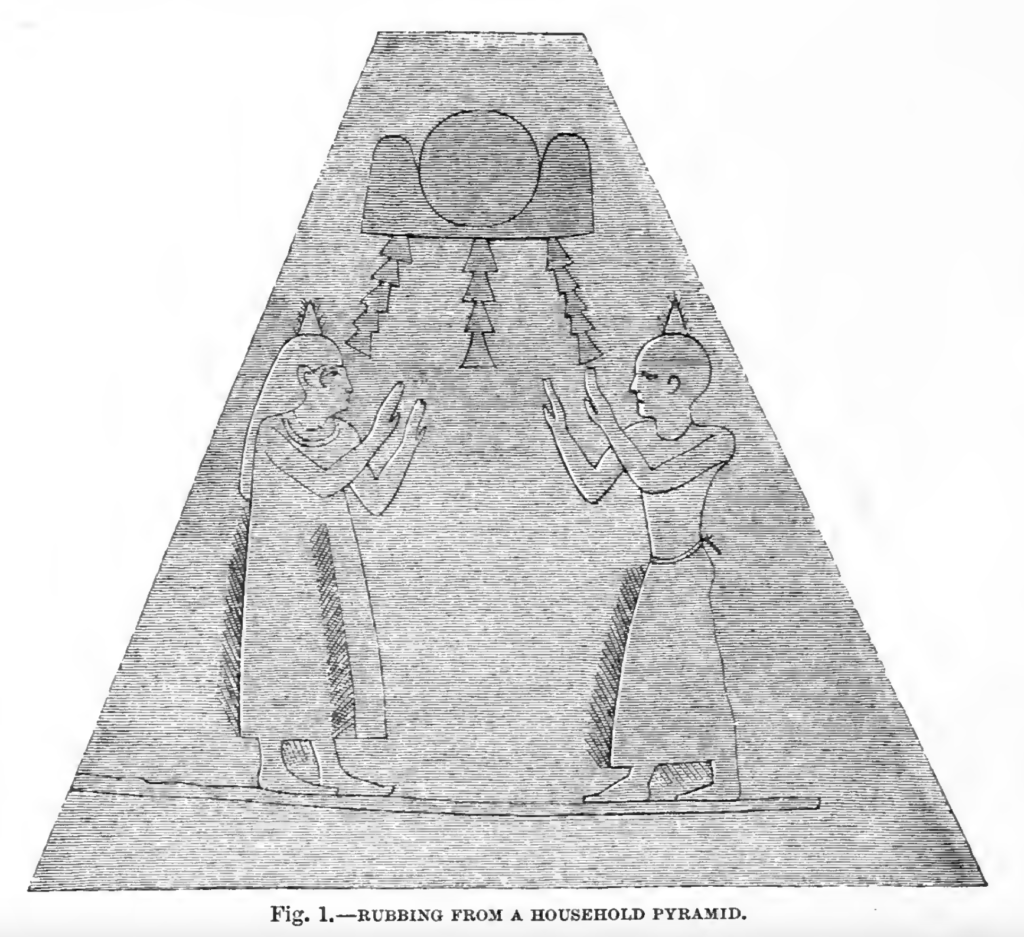

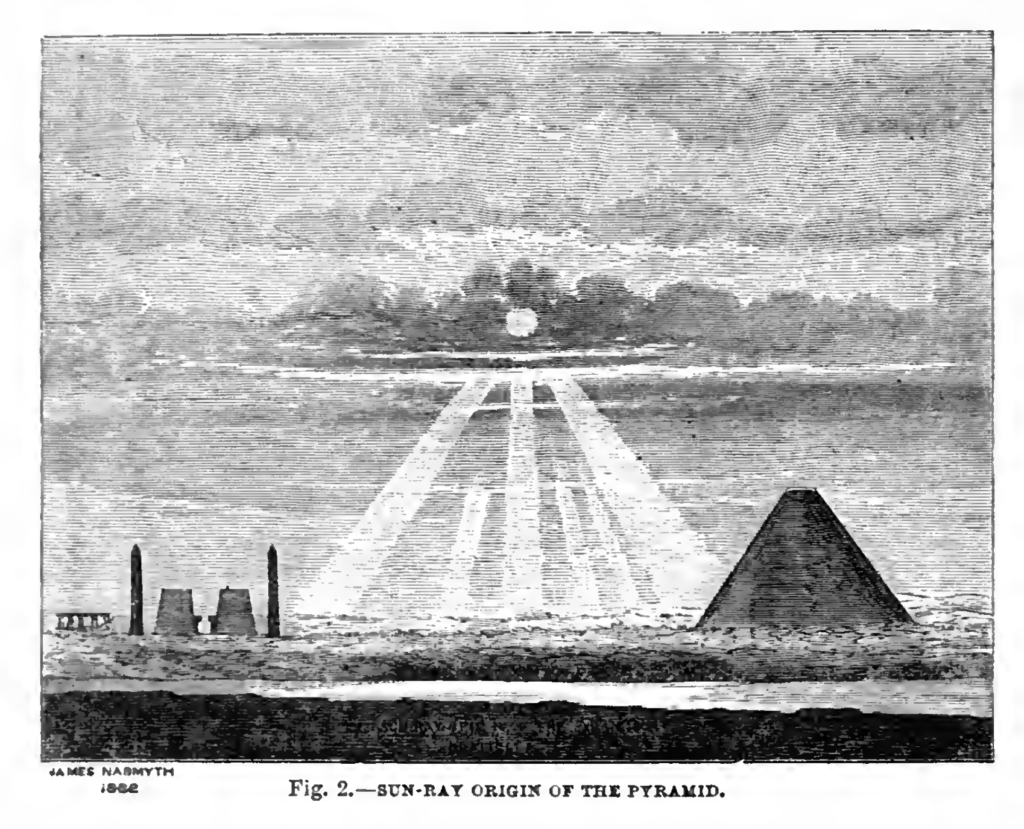

Constructed in the same era as Stonehenge, the Great Pyramid at Giza models many phenomena. A fairly explicit and well-documented one is the notable way the shape of the pyramid models the rays of the sun, which was worshipped as a god. In his autobiography, English engineer and pyramid enthusiast James Naysmith recounts:

On many occasions, while beholding the sublime effects of the Sun’s Rays streaming down on the earth through openings in the clouds near the horizon, I have been forcibly impressed with the analogy they appear to suggest as to the form of the Pyramid…. I met with many examples of this in the Egyptian Collection at the Louvre at Paris; especially in small pyramids, which were probably the objects of household worship. In one case I found a small pyramid, on the upper part of which appeared the disc of the Sun, with pyramidal rays descending from it … .

— James Naysmith 3

Crepiscular rays of light are parallel. But the laws of linear perspective dictate they converge on the vanishing point of the sun. The bottom-heavy pyramid shape (seen in cross-section here) is thus not merely a concession to gravity. It becomes an intuitive model for perspective projection, with a “false” vanishing point at its apex.

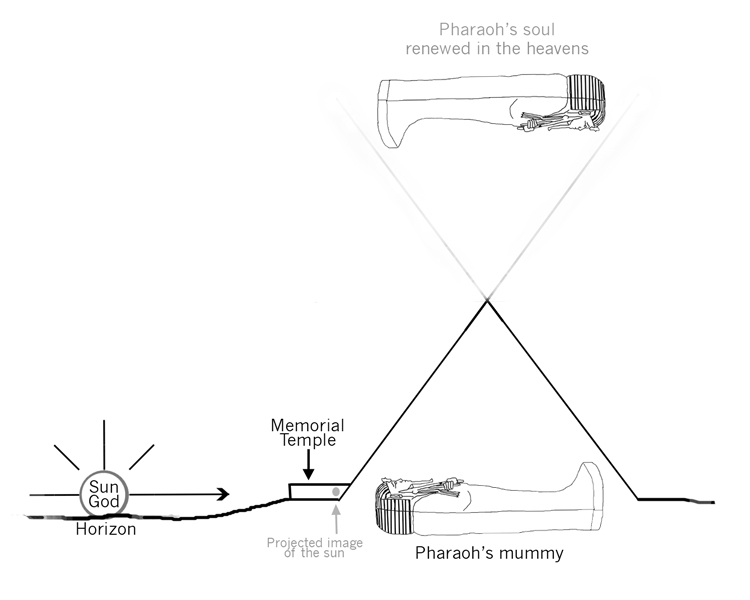

A camera obscura metaphor

Digging deeper, artist Matt Gatton has theorized a conceptual model of projection based on the camera-obscura phenomenon. 4 In this schema, the pharaoh’s mummy is metaphorically elevated to renewal in the heavens. In Gatton’s diagram, the pyramid metaphorically represents one cone of a camera-obscura projection that may have occurred in the memorial temple anteroom. The metaphorical projection is rotated 90 degrees to face the sky. One projection is represented by the stone of the pyramid, and the other half is implied.

Many theories concerning Giza, such as Robert Bauval’s pseudo-scientific mapping of the pyramid site plan onto the stars in Orion’s belt, have fallen into disrepute. However, the general idea that some physical correlation between pyramids and astronomical phenomena remains plausible. Egypt’s spiritual bent and societal structure would have supported such a monumental endeavor. Despite an attractiveness to mystics and crackpots, the pyramids without a doubt function as a model of the afterlife that so permeated Egyptian culture. To explore the Great Pyramid and the Giza necropolis, visit the NOVA website.

The afterlife

Egypt’s afterlife was a parallel universe constructed out of projections of the details of earthbound daily life, both grand and mundane, into the everlasting hereafter. Spurning the idea that you can’t take it with you, royal and aristocratic tombs contained all the material wealth deemed necessary for a proper afterlife, including servants, animals, and buildings. Eventually concluding it was a drastic use of resources to bury the real thing, detailed models were created, such as the one from an aristocratic tomb seen here. These provide insight not only on the Egyptian view of the afterlife but also on their earthly life.

Early architectural models

Architectural models were a staple feature of tomb adornment, not only in Egypt but also throughout the Mediterranean basin. Archaeologists found this model of a shrine in a Cypriot tomb. It probably served a ritual function at the burial, watching over the possessor’s soul as it made its final journey.

c 1975 BCE

Aristocratic burial devices used a considerable amount of an ancient country’s gross national product. The most outrageous use of this brand of “you-can-take-it-with-you” modeling was discovered in the 1970s with the unearthing of the Terracotta Army. The Army was buried in the tomb complex of the mytho-historical Chinese emperor Qin Shi Huang. The mausoleum is not completely excavated: legend has it that the central tomb chamber contains a model of Qin’s empire, complete with rivers made of mercury and a glowing rendition of the heavens inlaid in precious stones.

Such tomb-making fulfilled a spiritual purpose, but it also served a political agenda. As projections of political power, the tombs created a cultish awe within ancient people for their leaders. This allowed royalty to maintain dynasties and bloodlines for centuries. Memorial building, modeling the power of the leader, became a staple of empire, from Egypt through Rome and beyond.

Renaissance and Enlightenment

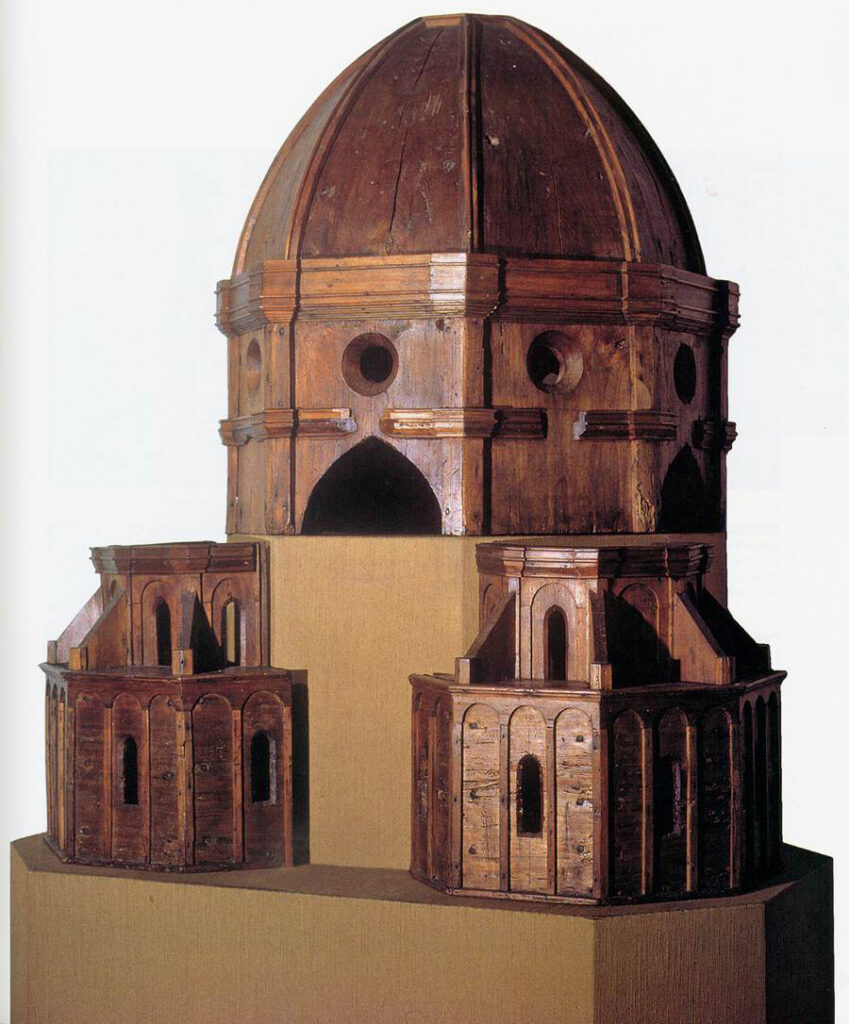

Brunelleschi’s Duomo

In 1292, Arnolfo di Cambio began one of the most important works of architecture in history. The Basilica di Santa Maria del Fiore, more commonly known as the Duomo of Florence in Italy, was a source of civic pride for the up-and-coming city-state. Florentines so approved of di Cambio’s design that visual records of the day show the Duomo as a fait accompli. This, despite that the plans called for a dome so large that no one knew how to build it.

As the need for an answer to the inevitable question of the dome’s structure became more urgent, city leaders held a competition at the dawn of the Renaissance, the early 1400s. Florentines were desperate to discover a builder who could find a way to complete the visionary design, which explicitly did not call for the use of Gothic buttresses. 5

The competitions

Competitors used detailed models to communicate ideas for the structural design. Filippo Brunelleschi had by far the most innovative design. This double-nested dome knit itself together with internal stiffening ribs ringed with enormous stone and iron “chains” counteracting spreading forces like the iron hoops of a barrel. Brunelleschi, who wanted to maintain control of the politically volatile project, intentionally left the winning model incomplete.

City fathers held a second competition for the lantern, the small structure atop the dome. Again, Brunelleschi used a model to win. Structural engineering science would not be developed until centuries later, so like other cathedral builders, Brunelleschi relied on intuition. He informed his intuition with high-fidelity models that predicted structural remedies. The modeling method was so successful the Duomo, the largest brick dome ever constructed, remains sound centuries later.

The orrery

The Renaissance of the 14th — 17th centuries CE ushered in the unprecedented era of respect for science and reason in the 18th century known as the Enlightenment. Models were used to create expressions of newfound scientific knowledge on many fronts. Although earlier ones exist in the historical record, the mechanical model of the solar system called the orrery became quite popular during this era.

In most orreries, positions are usually relative and not to scale. Despite this, some orreries achieve real-time or true scale modeling. The Eisinga Planetarium in Franeker, the Netherlands, is not, in fact, a planetarium but a real-time, room-sized orrery, one of the largest in the world. It is run by a pendulum clockwork.

Contemporary versions of the orrery include the 10,000-Year Clock at The Long Now Foundation. For Google Earth in 2016, user Barnabu’s add-ons included animated orreries. There’s also an interactive web-based orrery at Solar System Live by John Walker. This website is a bit old-school, but if you tweak some parameters you can get interesting results.

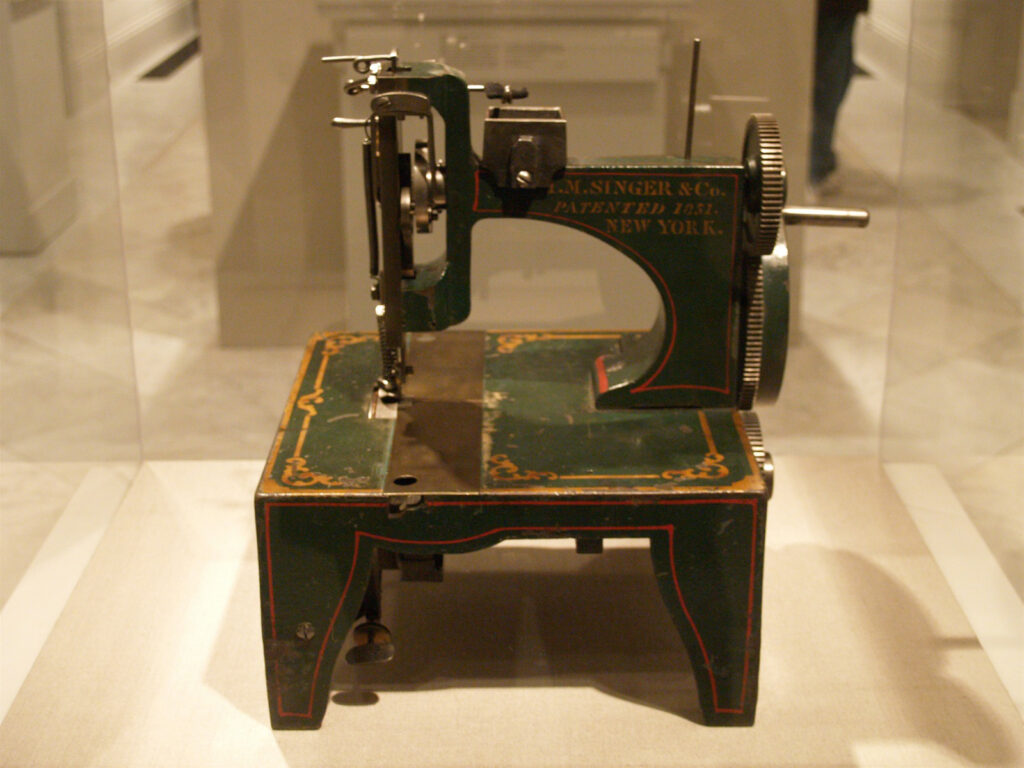

Business and pleasure

Before the advent of modern communication methods like photos or videos that could demonstrate the effectiveness of an invention, the Patent Act of 1790 required a patent seeker to submit a working model of an invention along with his or her application to the U.S. Patent Office. Professional model makers would create elaborate, well-crafted, finely finished models out of expensive materials. The theory was that a fancy presentation would secure a patent.

Almost a century later, the burden of keeping the models became overwhelming. The Patent Office abolished the requirement and liquidated its storehouse. Some patent models ended up at the Smithsonian Institution. The remainder landed in private hands, with the largest collection found at the Hagley Patent Model Museum, formerly the Rothschild-Petersen Museum.

Rothschild-Petersen Patent Model Museum on the History Channel at Vimeo

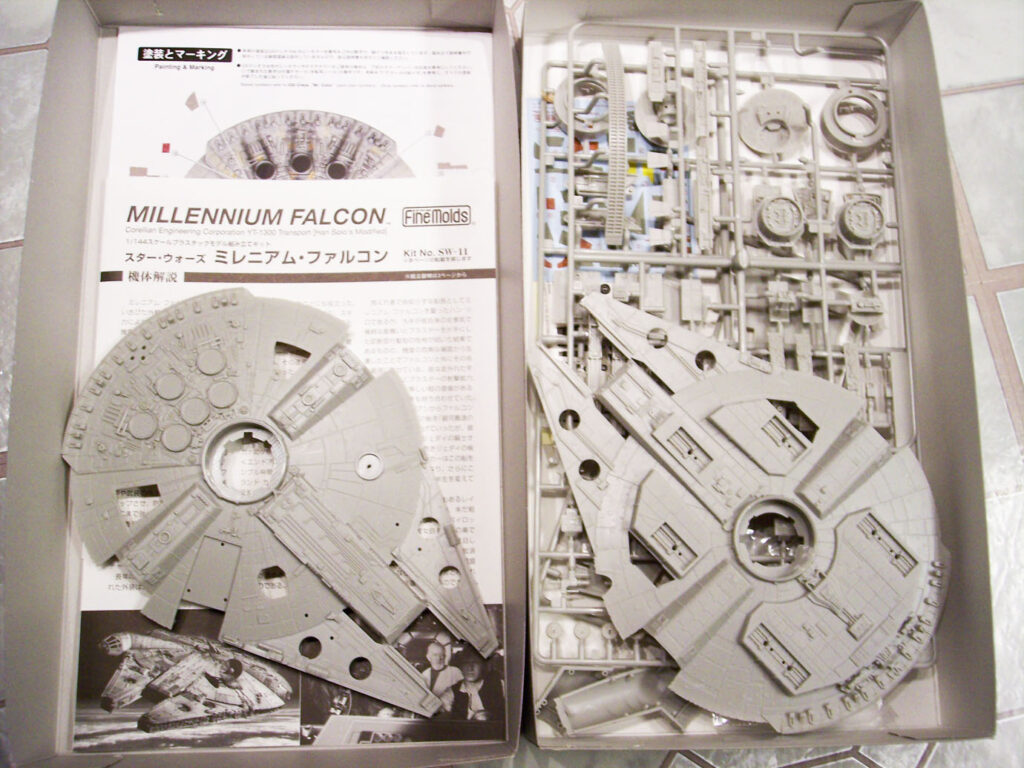

The death of the patent model was not the death of modeling by any means. Modelers turned to the hobby market to ply their trade. They created objects ranging from finished die-cast metal vehicles to plastic put-together spacecraft. We can see the 20th Century as a kind of Golden Age for hobby modeling. Models such as the famous Citroën toy cars were marketing tools created by the manufacturer to introduce the idea of car ownership to future drivers. Indeed, the pleasure of hobby modeling instills a sense of vicarious ownership. If you can’t actually have the Millennium Falcon, you might fantasize that you do when you finish the model.

Enter digital modeling

Metaphors to drafting

Digital visualization was limited at first by the mechanical visualization modes that preceded it. At first, CAD (computer-aided drafting) tried to emulate T-square and triangle drafting. Over time, programmers and users realized they had an entirely new way of looking and making. Because of how the computer handles information, people realized that they could do so much more than simply emulate a 2D drawing process.

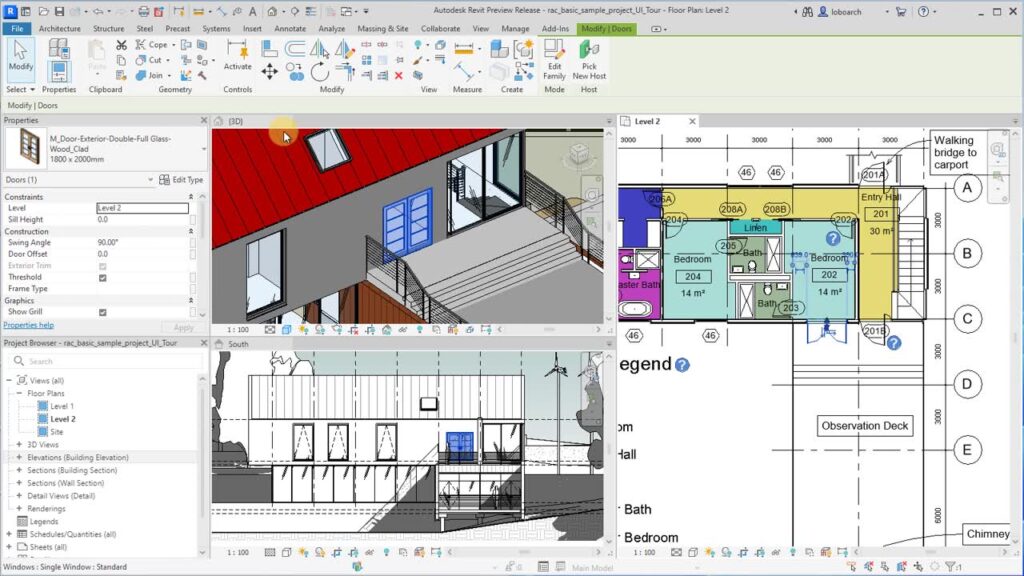

Among the transformative tools that evolved out of early CAD were 3D models that could be looked at from a variety of angles. This made bulky and expensive architectural models harder to justify, if not outright obsolete. 4D or time-based modeling evolved out of this. Designers could model objects and cameras to change over a timeline, transforming not only design visualization but also entertainment. Entire industries, such as gaming and cinematic CGI (computer-generated imagery), have developed out of this.

Virtual building

More recently, innovations in manufacturing and building at large scale have come to depend on 4D modeling. Designers use information modeling to control part inventory and scheduling in shipbuilding and aircraft construction. In architecture, building information modeling (BIM) programs such as Revit use libraries of parts and animated workflow to manage a job site. Boeing began using animation and information modeling in 2006 to present a “virtual rollout” of the 787 Dreamliner. This kind of modeling can easily reveal design flaws. If a worker can’t reach a bolt, engineers can redesign it before such an issue becomes a thorny and costly one.

This concept of the virtual build processes (VBP) has allowed artists such as Richard Serra, Claes Oldenburg, and Coosje Van Bruggen to create large-scale, geometrically complex work. Serra discusses the role of model-making in his work at this link.

A word of caution: the tactile word often has the last laugh. Read this account of Claes Oldenburg and Coosje Van Bruggen’s ill-fated Collar and Bow for Frank Gehry’s Disney Hall. All the modeling in the world didn’t predict the dicey legal outcome!

- In a layer of modeling irony, It should be noted that, for most visitors, Lascaux is a modeled experience. Instead of visiting the actual site, people are directed to Lascaux II, a 1-to-1 replica of the original cave constructed after microbial damage from exposure to visitors was discovered in the original site. Researchers such as Jègues-Wolkiewiez have access to the original for scholarly purposes.[↩]

- More irony: Stonehenge is something of a modeling in-joke to fans of This Is Spın̈al Tap, Rob Reiner’s famous rock mocumentary. After the band gives an artist incorrect dimensions for a model to accompany a lavish number about the 18-foot-high megaliths, hilarity ensues when the prop descends dramatically out of the stage loft — and the 18-inch-tall microlith is dwarfed by everything on stage. Lesson: watch your units![↩]

- Naysmith, James. James Naysmith, Engineer; An Autobiography (Classic Reprint). John Murray, London, 1883. Digital reprint Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010. p. 432.[↩]

- The camera-obscura uses a pinhole opening in an otherwise darkened space to create a breathtaking inverted image of the world outside; it is an early technology we’ll explore in depth in Chapter 12.[↩]

- Although buttressing (a kind of structural rib set perpendicular to a primary wall) would have solved the problem easily, Italians considered the Gothic style and methods to be aesthetically unpleasant and culturally foreign.[↩]