“Improvements” changing livelihoods

In our exploration of the Jacobite period and its aftermath, we’ve run across many historical descriptions of life in rural Scotland and the nature of farm life. Many sources describe the hardships of subsistence agriculture, which as recounted are hard enough without any other encumbrances.

But imagine that life overlaid with an exploitative system of land management, in essence feudal in nature, and its evolution through land “improvement” which somehow made things worse by breaking up common lands into “enclosed” parcels. The commodification of the commons seems to be a refrain we’ve suffered through many times as capitalism continues its relentless march to commodify every aspect of our lives (except maybe air, but watch this space as we prepare to endure a looming climate crisis being decidedly ignored by our boomer elites… but I digress). Suffice to say such exploitations are nothing new.

These historical descriptions bear witness not only to the distinctions made among classes, but also between gender roles, with the farmer’s wife surely getting the short end of that stick. We’ve seen how the forces of history percolate down into the day-to-day decisions people make as they live their lives.

In short, we can see our time reflected in theirs, although to be sure, the life my family lives today in Philadelphia is a comparatively privileged one, based in no small measure on the incremental struggles and decisions made by my ancestors to improve their lot, despite hardships both natural and man-made.

Polymath ancestors

Our research has revealed that members of a Scottish farming family were not simply farmers; they were polymaths. They could not, for example, simply drive to the Tesco (the U.K.’s answer to Walmart) and pick up fast fashion to clothe themselves. For a proper article of clothing, one had to understand every part of the process to make it, from animal husbandry, to sheep shearing, to spinning, to weaving, to “waulking” cloth (a communal, ritualistic process to soften wool, involving singing to keep rhythm, so add music to the mix), and assembling the garment, though to complete the process we should add mending it to extend its life, and washing it — by hand, not in a machine.

Many of the skills acquired simply to survive eventually evolved into specialties. A particularly talented seamstress could supplement the family income with a second vocation crafting fine linen (once all the farming chores were done, of course). Off-season or side work as a taverner, cobbler, post-master, carpenter, mill-wright, or any number of occupations could take the edge off of the limited economic opportunity imposed by the systemic and environmental limitations inherent to subsistence farming. A person’s gotta eat.

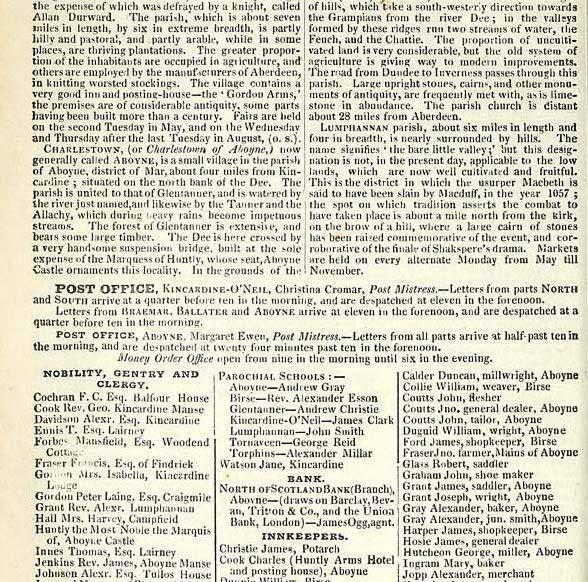

The Scottish Postal Directories

A wonderful resource that illuminates this aspect of life in 19th century Scotland can be found at the Scottish Post Office Directories. The National Library of Scotland has digitized and placed these directories on the web for researchers to dig through. Many of the children of the post-Jacobite Cromars and related families are found in these publications, beginning in the 1820s and moving forward through the century. These documents tell the story of neighbors living lives in a granular way. Without the directories, if one wishes to fathom neighborly relationships, one has to rely on careful comparisons of dates on headstones in a burial yard. With the Directories, complex patterns emerge in a high resolution snapshot of these folks’ lives. We can even get a picture of the context, as many of these Directories contained lengthy descriptions of the settlements they catalogue.

Below, I’ll share several pages from the Directories containing Cromars, starting about 1825 and concluding in 1905. Where I can, I’ll identify the Cromars listed and cross-reference them to information seen in other posts in this blog.

James Cromar | Kincardine O’Neil

James Cromar is listed above as post-master at the Kincardine O’Neil Post Office. A second James, perhaps the same one, is listed under Jas. as a linen draper and a grocer. A linen draper was a wholesale dealer who sold cloth for people to buy and make their own garments. It’s not unheard of for persons to occupy many trades in these directories — but there do seem to be many James Cromars in the region at this time! This James may have been born 1802 in Kinker, son of Alexander Cromar (son of Robert Cromar and Isobel Ley) and Christian Cromar (lone daughter of Robert Cromar and Margaret Nichol), all of whom we met in the post prior to this one.

It’s interesting to note that Christian is a longstanding Principal Officer of the Post, serving from 1799 to her death in 1859. This could explain how the Cromars corner the market on this occupation in the region, as we’ll see in the next Directory page.

1 | Map of Kincardine O’Neil showing location of Post Office in the mid-18th century | Screen-capture from Genuki

2 | This gift shop may occupy the site of the Post Office (and may in fact be the structure itself) | Stanley Howe, 2014, geograph.org.uk CC BY-SA 2.0

Alexander, George, and Robert Cromar | Kincardine O’Neil and Charlestown (Aboyne)

Here we note Alexander Cromar occupying the office of post-master in Kincardine O’Neil and George Cromar doing so in Charlestown of Aboyne. The list of shopkeepers also notes Alexander — presumably the same one — as a general dealer. George — again, presumably the same — is listed as a shoemaker in Charlestown. A third family member, Robert Cromar, is listed as a wright, an archaic term for a maker or builder, though this doesn’t specify of exactly what. Given the family history, we might presume he is a member of a building construction trade.

In 1837, these Cromars are too late to be the brothers Alexander, George, and Robert mentioned in the previous post as sons of Robert 1717, and given death data for George 1772-1829, this Alexander and George pair are not the sons of Robert 1752. This George is claimed as the son of Peter 1757 and so is the grandson of Robert 1717. Alexander may be the son of Alexander and Christian, and therefore the brother of James mentioned in the previous Directory page. Robert may be one of two sons of Alexander and Christian, one born in 1798, the other in 1815.

“Mrs.” Cromar and Peter Cromar | Kincardine O’Neil and Lumphanan

Postmistresses

This “Mrs.” can be none other than Christian Cromar, who we’ve mentioned has cornered the postal market for her family. Two other Cromars are mentioned on this page, one being Robert, a wright and glazier, who is probably the same wright mentioned in the 1837 Pigot directory; the designation glazier here confirms our assumption he is a builder, as glazier refers to the craft of making windows.

Ground Officers

The second, Peter Cromar, is noted as a senior ground officer. In Scotland under the tenant system, this officer, sometimes going by the name maor, was employed by a large estate to supervise the activities of tenants. According to a forum entry at RootsChat: “As well as advising on the resolution of disputes and replacement of tenants… he will have kept the crofters up to date with duties such as fencing and drainage.” The ground officer would also be responsible for ensuring no illegal hunting, fishing, or foraging occurred, and was charged with the unsavory task of evicting tenants who were in arrears. It would seem a ground officer functioned a bit like a private constable.

In Reports of Cases Decided in the Supreme Courts of Scotland and in the House of Lords on Appeal from Scotland, Volume 10, edited by M. Anderson in 1838, we find more detail about Peter’s position. The compensation for such a job would be a reduction in annual rent by between one-third and one-half of the rate; this text recounts a case where a tenant was granted £5 for the position, deducted from an annual rent of £12, and goes on to describe the economy of estates as a predominantly in-kind arrangement:

… leases stipulating in whole or in part for services to be performed by the tenant, have long been sustained in Scotland, as exemplified in the case of cottages and pendicles very frequently let for so much money and so many days’ shearing, or so many carriages of peat, coal &c., and it has never been understood that the landlord could decline theses services and exact money. The service of a ground-officer on extensive highland estates is as necessary and as well recognized as any service performed by tenants under predial contracts.

Auchinhove

In Lumphanan in 1846, the estate employing Peter was most likely that of Sir Francis Farquharson, who we encountered in John Cromar and Ann George: rebels who broke free a few posts ago. It would appear much of the old Auchinhove estate which had been seized from the Baron of Auchinhove as punishment for his part in the Forty-Five was eventually acquired by the Farquharsons, who owned many properties, including the farm at Bogloch, which this Peter is confirmed as a resident thereof.

George Cromar | Aboyne

Shoemaker George Cromar, who we saw in the Pigot Directory of 1837 above, is seen again here. A decade later, in 1847, Charlestown is going by the name of Aboyne. He is no longer the post-master, thus shoemaking was perhaps quite profitable at this time.

George, Peter, and Robert Cromar | Lumphanan

The George Cromar referred to here as a farmer at Milton of Auchlossan is my third great-grandfather, written about in George Cromar and Ann Meston: tragedies and mysteries. Peter is the same ground-officer found in the 1846-8 Bon-accord Directory above. The Robert referred to as farmer at Auchinhove House, possibly a reference to the farm run directly by the estate (which in the second half of the 19th century became the Home Farm north of the Easter Mains), is not one of the five Roberts untangled in the previous post. This Robert appears to belong to that branch of the family found at Stone 39 in Kirkton of Aboyne burial ground, and could likely be Robert Sherrat Cromar, 1826-1910, who married Elizabeth Grieve in 1852 and bore, among others, a son Farquharson Shaw Cromar, all of whom are buried there.

Our brush with nobility

Robert’s father, also named Robert, born 1793, married Mary Sherrat in 1823. Father Robert evidently passed away sometime between 1826, the year of his son’s birth, and 1830, when Mary is recorded married to James Shaw. Mother Mary has somewhat convoluted ties to the eminent Farquharson family, being the niece of Christian Spring who caught the eye of an elder Archibald Farquharson, the 7th Laird of Finzean, himself the son of the Francis Farquharson mentioned above. This is as close as the Cromars ever get to the peerage, and the family was so honored by the marriage of Christian, a humble daughter of a gardener, that this is why we see the name Farquharson persist as both a given and middle name for a quite some time along the entire branch. Ah, reflected glory!

Christian lived long after Farquharson’s death at Auchinhove Cottage, which is really a substantial 2-story dwelling that belies the term cottage, and it is believed her niece Mary lived there as well, or at least nearby. This would explain Robert’s presence as an estate farmer at the house farm until the early 1900s.

Top right | The Mill Farm looking north from the road. | Ann Burgess, 2017, geograph.org.uk, CC BY-SA 2.0

Bottom left | Auchinhove Home Farm, midway between the Mill Farm at south and Auchlossan Cottage to the north. | Ann Burgess, 2017, geograph.org.uk, CC BY-SA 2.0

Bottom right | Bogloch Farm, between Milton of Auchinhove to the east and Peel of Lumphanan to the west. | Ann Burgess, 2017, geograph.org.uk, CC BY-SA 2.0

Christina Cromar | Kincardine O’Neil

The Christian Cromar who served as the longstanding postmistress in Kincardine O’Neil had died in 1859 according to several sources indexed at FamilySearch. This may have been her daughter, also Christian but here rendered as Christina, born 17 December 1809 and christened 5 January 1810. We’ve seen variations on names like this persisting even up to my great-grandmother Christiana Robb, who was also rendered Christina and Christian in various documents.

Some repeat entries…

Peter Cromar of Bogloch farm from above makes another appearance in Worrall’s directory…

… and Peter makes yet another showing, this time with George, in Slater’s directory and generalizing their location to Lumphanan. The George listed here is George 1825-1921, son of George Cromar listed above in Cornwall’s directory of 1853-4. But we’re not done with these fellows yet…

… because we see them yet another time: George and Peter in the 1886 edition of Slater’s, though this time specifying Milton of Auchlossan and Bogloch respectively.

… and a final entry: George, Andrew, and Robert | Lumphanan region

In this final directory installment, we see a pair of familiar faces and one newcomer. George Cromar at Milton of Auchlossan and Robert Cromar from Auchinhove home farm have been previously listed. Andrew, together with “Mrs.” Jane, are located at Bogloch. Andrew appears to be the son of Peter Cromar, late of Bogloch and listed above. His presumed wife and any potential children have not yet been found in the record.

Returning to the direct line

Many of the Cromars in these directories are uncles and cousins who will later figure in the Cromar diaspora I hope to explore once this investigation of my direct line has run its course. It’s been fascinating to see how the family has fared along other branches, from monopolizing postal services to garnering tangential brush with landed gentry. These directories have enlightened us as to the lives lived beyond the post-Jacobite period as the nation of Scotland settled into a Union with England that some would characterize as uneasy, others might classify as unequal, and still others accuse of being outright colonial.

Whatever your take might be on that topic, we’re transitioning away from the lives of such as my sixth great-grandmother Jannet Dun and my fifth Janet Bonar, and moving into the world occupied by my fourth, Ann Cromar. We briefly explored her life in All the Johns and Anns: the case for the parents of George Cromar 1792-1871, but we’re going to honor her contributions to the family history by seeking out greater detail in our next post.

Leave a Reply