AUTHOR’S NOTE: New information and research has invalidated certain conclusions about the identity of John Cromar in this post. You may read about this development at Ann Cromar redux — or reconsidered? and at Ron Cromar and me. Because this journal is about the real-time process of researching and developing a family history hypothesis, and not the hypothesis itself, I have decided to keep the contents unaltered, save for this caveat. I hope in doing so to illustrate how the process can lead to reasonable yet flawed conclusions, and how one can avoid the pitfalls of confirmation bias by keeping an open mind when presented with new evidence. The bottom line: the identity of son John discussed here is incorrect, but as you’ll see in the posts linked above, I am fortunate this does not invalidate the overall bloodline being established.

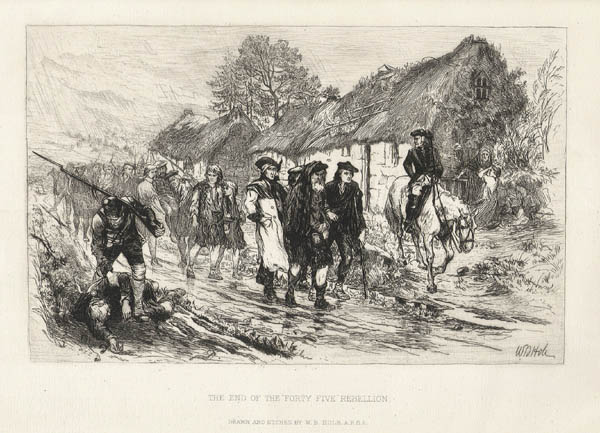

No matter how physically distant someone may have been from the slaughter at Culloden in 1746, it’s fair to say not a single person in Scotland escaped the effects of the final defeat of the Jacobite uprising. The Howe of Cromar lies some 80 miles east and south of the battlefield, separated by rugged Highland terrain, but this hardly means it was on the sidelines. Many people are unaware the Jacobite cause was taken up all over Scotland, not simply in the Highlands near Inverness, and it therefore comes as a surprise that nearly half the troops mustered by the Jacobites were not from the Highlands, but from eastern coastal and midland counties.

Jacobitism in Aberdeenshire

Indeed, Jacobitism had been a part of Aberdeenshire politics long before Culloden. Many Aberdeenshire nobles, among them John Erskine, 6th Earl of Mar, had cast their lot with the Stuarts as early as 1715. The Howe of Cromar lies at the nexus of Highland and Lowland, and as such played a strong supporting role in the Rising.

In Aboyne, for example, Mar conducted a tinchal — a great hunt — to which he invited many Highland chiefs, on 3 September 1715. This hunt was a ruse to cover a meeting at which he proclaimed a desire for an independent Scotland and led a discussion among the Jacobite nobles to plan an uprising, which began 3 days later at Mar’s Braemar estate and ended a year later with Mar fleeing permanently abroad, a Writ of Attainder for treason having been passed by Parliament for his disloyalty to the Crown and strategic blunders on the battlefield under his belt.

Later, during the 1745 uprising, Auchenhove Castle near Milton of Auchinhove, a stone’s throw away from my ancestors in Milton of Auchlossan near Lumphanan, was destroyed in 1746 by the Duke of Cumberland’s army to punish Patrick Duguid, Baron of Auchinhove, for his efforts to support the Jacobites by supplying a company of men from Lumphanan for the northern army. It is unknown if a Cromar descendant was one among the 50 or so that their Baron and likely landlord supplied for Culloden.

The hypothesis of Glencoe

Even though no direct participation in these two Jacobite uprisings by members of the Cromar family can yet be established by historical record, the unrest stirred up by the first Jacobite rising of 1689 and culminating in the Massacre of Glencoe may have directly led to the Cromar’s presence in the Howe — leastways the branch of the family from which my ancestors emerge.

As we’ve recounted elsewhere, the family legend supports a theory that the kin of my sixth paternal great-grandfather, Peter Cromar, participated in a post-massacre diaspora, a hypothesis this blog intends to either prove or debunk. Regardless of the outcome of this exploration, we can say for certain the citizens of the Howe, including my forbears, were witnesses to this history and bore the brunt of its outcome, if not on the battlefield, then in the chaos of the aftermath.

Record-keeping and the Church

That chaos is reflected in the fact that record-keeping, ordinarily a meticulous occupation of the Church, becomes quite scattershot in this time period. While such accounting was a function later ceded to the secular state in the Census records started in 1841, prior to that time the Church of Scotland, alongside other denominations, kept a chronicle of the souls under its watch: births, banns and marriages, penitent action for sin as well as death records and even the rental of mortcloths that would adorn coffins at funerals. In many ways, the Church was the State in a manner Americans have a difficult time comprehending, given the separation between those institutions encoded in our founding (and which many, being ignorant of the unhappy consequences for the history of nations like Scotland, wish to see reunited here).

Record-keeping is disrupted for many families searching for Scottish roots during the Jacobite period. Accounts are lost or never created, people are displaced or killed, Highland and Lowland “Clearances” — for some, a thinly euphemistic term for genocide — are conducted, and aliases are concocted to avoid the wrath of authorities hell-bent on avenging perceived treason. Unless one manages to discover a direct line to nobility, much we could learn about common folk swept up by the forces of history gets lost in the turmoil.

Agricultural praxis

As tenant farmers, the Cromars are far removed from a nobility who celebrated their status with elaborate family trees and heraldry documenting dynastic lines. In the late 1700s and early 1800s, a Scottish family like that of my fourth paternal great-grandparents John and Ann Cromar toiled under the lairdship of said nobility on an enclosure, a parcel developed under a crofting system of land tenure that had eventually replaced the medieval open-field and run rig system during their parents’ era.

2 | Remains of a runrig on the Isle of Skye | Adam Ward, 2007, CC BY-SA 2.0

3 | Illustration of runrigs outside Haddington in Theatrum Scotiae, John Slezar, 1693 | Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

The boundaries of enclosure established during the Scottish Agricultural Revolution strongly define the landscape even to this day. The lives my ancestors lived on these plots of land were labor intensive and harsh. Add up the influences of the hierarchic land tenancy system, the itinerant farm and domestic servant “market,” non-existent social mobility, and chaotic political and religious upheaval, and it’s easy to see how archiving of records might take a back seat to the effort of simply surviving.

A comparison of the enclosure land tenancy system in the mid-1800’s compared to today’s privately owned plots of land. | Screen-captures from genuki.org.uk

The uncertain task ahead

We recall how difficult it was in our prior post to identify the John and Ann Cromar who the record, supplemented with burial-ground archaeology, allow us to deduce as the parents of my third paternal great-grandfather, George Cromar. Having identified with a cautious degree of probable certainty the identity of my fourth great-parents, we face the daunting task of uncovering of the next generation out.

With Scotland in turmoil before Culloden and in tatters afterward, I will candidly acknowledge that we could easily at this point run into another brick wall — but one that, this time, we won’t be able to breach. Nevertheless, here goes…

Robert Cromar vs. Robert Cromar vs. Robert Cromar

The go-to first resource here is the established Family Search branch of this family, which we’ve been working down from Charles Robb Sr. (gf), to Theodore James (1ggf), John (2ggf), George (3ggf), and John (4ggf). This is a crowdsourced resource and therefore should be approached with extreme caution, though it seems the community here takes far greater care of substantiating claims with citations from historical primary sources than others at sites of its ilk. I rarely and cautiously contribute changes myself, doing so only when I have incontrovertible proof to back it up. Not every entry is treated with the same care, however.

As we explore the Family Search entry for John Cromar 1755 of Aboyne, we find a parental link auto-generated by Family Search algorithms to a father: Robert Cromar. The algorithm may have recognized this relationship from a christening record of 16 September 1755 with Robert named as father. All good, but which Robert? The mother is not listed in the birth record easily obtainable at the ScotlandsPeople website so that isn’t a bread-crumb we can cross-reference.

Clicking on the link at John’s entry for Robert 1717 of Aboyne, we open a writhing can of worms.

Dale’s dilemma

Anything that could have gone wrong with this entry has gone wrong with this entry. Among the many troubling details, we see in the collaboration comments this note titled Robert Cromar vs. Robert Cromar vs. Robert Cromar written in 2015 by Dale Young Cromar, a heretofore unknown distant cousin in Utah who passed away in 2018:

Just had a conversation with Kevin Cromar, [email protected], Facebook, who has been trying for a long time to figure out Robert Cromar and Robert Cromar and Robert Cromar. There are at least two Roberts if not three. They have been merged down to just two with the same parents and the same birth year, NOT POSSIBLE. The sources for these three Roberts leave much to be desired for clarity. But there are enough details in Kevins hands to know that the way they are in Family Tree right now is messed up. Somehow a new PID was created and all the old work done for them has been lost and new redundant work has been put in their place. Most of the basic outline of the facts was figured out by Rozella Cromar Jordan years ago. The refinements added by Kevin have been lost by merging records that should not have been merged. The final story has not been written for the three Roberts. More research is needed. And lots of unmerging and who knows what else must be done to make them correct again. Please communicate with Kevin by email if you would like to help fix the Roberts [email protected].

Stale breadcrumbs…

Dale mentions two relatives here, Rozella Cromar Jordan and Kevin Cromar. At this point, the research takes on an aspect that makes me feel uncomfortably like a stalker! I discover that, while Rozella, a professional genealogist, passed away in 2001, Kevin appears to be among the living with clear contact information, so watch this space. But the search for Rozella turned up an interesting link to another deceased researcher with whom we are familiar: Ron Cromar. This Genealogy.com thread conspicuously ties together the identity of many of these researchers at the same time it provides some insight into the notes gathered by Ron, which I’m still itching to get ahold of. In a conversation spanning nearly a decade, from 1998 to 2007, contributions to this thread lead to some breadcrumbs, stale and unverifiable though they may be. An anonymous user in late 1999 writes:

I too am a descendant of Alexander Ramsey Cromar and found his gravesite in the Church Cemetary [sic] in Tarland, Aberdeenshire Scotland in 1989. Unfortunately the Rector was away on holiday so I couldn’t do any further research. You could try Ron Cromar at “[email protected]” who lives nearby and has quite a bit of information about the Cromar family. I believe he has information going back 3 or 4 more generations.

To which a user named Nan Christensen replies in July 2007:

I am also a descendant of Alexander Ramsey Cromar. Here is a copy of a letter I received from Ron Cromar in Scotland Last [sic] year I hope it helps you.

[Quoting from Ron] will [sic] try to help: ALEXANDER RAMSAY CROMAR chr 9th Sept 1807 and married ISABELLA NIVEN 2nd Aug 1828 and he died 5th Nov 1846

ALEXANDER parents were GEORGE CROMAR AND JEAN GILLESPIE but GEORGE re-married to a MARGARET BARCLAY

GEORGE was a schoolteacher of BANKHEAD, ABERDEEN and his FATHER was ROBERT CROMAR and his MOTHER was MARGARET SMITH, they were married 27th Oct 1771 at ABOYNE

This may be wrong Nan but ROBERT born about 1717 and was firstly married to JANET DUN then married to MARGARET and his parents were PETER CROMAR and JANET BONAR.There is a man who has details of all the CROMAR’S [sic] and his name is DALE, he is the nephew of the late ROZELLA CROMAR JORDAN in UTAH. Unfortunately my computer was changed and I lost all my addresses so I am hoping that Dale will write again. Hope this will be of help to you, mind you a lot was guess work from papers sent to me.

… and tangled destinies

Ron’s letter to Nan provides the first clear — though unprovable — connection between Robert 1717 and his father, the elusive Peter Cromar. But the jury is not out. Back at Robert’s Family Search page, we see assertions of TWO competing fathers: Peter 1690 of Aboyne, and a Robert Cromar 1677 of Leochel-Cushnie and later of Oyne as the father of several children. On Robert 1717’s christening record in Oyne, this father appears as Rot., a possible abbreviation for Robert. Robert 1677’s page claims a marriage to Jean Matthewson and several other children in Oyne.

At first, one might be tempted to confuse Oyne as a typo or shorthand for Aboyne, but a quick review of the map reveals it is a discrete settlement several miles north of Lumphanan — and close to another town with an anomalous relationship to the Cromars: Clatt. Readers of this journal will recall that a Cromar with no surname is recorded, with a John Cromar listed as father, as christened in Clatt in 1692 on Peter Cromar’s birthday: 8 September. What can all this evidence so far north of the Howe suggest, beyond confusion in the record? Does it confirm Dale Cromar’s assertion that several Roberts have been conflated to one, leading to tangled destinies? How might we untangle them?

Teasing out the Roberts

My first stop is the record at ScotlandsPeople. The Robert we seek will have been born within a range that allows him to be the father of John Cromar 1755. We find Robert 1717 of Oyne, son of Rot., of course. But no other eligible Roberts are in the birth records.

Marriage records are no more helpful, with no eligible Roberts marrying anyone in the record on time for John’s birth. We do find one Robert marrying Margaret Smith in 1771, in Aboyne, fueling the hypothesis mentioned by Ron Cromar in his letter to Nan Christensen. Ron’s suggestion is that Robert 1717 was the one who joined Margaret in 1771 in a second marriage and had issue, but I find these dates somewhat fantastic. Would a 54 year old farm laborer remarry and have more children at an age when he could reasonably be a grandfather, or even great-grandfather?

Death records are even more sparse. In this era we find just one death record, and that one in the city of Aberdeen, implausibly far to the east, in 1798. Some family trees have conflated Robert 1717 with this Robert d. 1798, but geography makes this connection suspicious.

This is where I think Dale Cromar had it right. These are three Roberts: one who was born in 1717, one who married Margaret Smith in 1771, and one who died in Aberdeen in 1798. In Family Search and in other family trees, we see people (even Ron Cromar himself) concluding these are one. But that conclusion assumes absence of a record is absence of a person.

This is a deeply unsatisfying brick wall.

Marischal College to the rescue, sort of

Utterly stymied by the lack of a positive identification of the Robert, father of John 1755, in our otherwise reliable database at ScotlandsPeople, we have to turn elsewhere for more stale breadcrumbs. In looking through the notes at Family Search, I recalled seeing an odd reference to a document from Marischal College in Aberdeen. Founded in 1593, its humble secondhand buildings were in service during the 18th century until replaced by the far more ornate granite structure that it occupied through the 1990s. The view in the image above would have been familiar to the Cromars, as they had a few fortunate sons attend the College, including a James Cromar in the 1780s.

James, son of Robert

This James turns out to be the son of a Robert Cromar from Lumphanan, seen in this record from Fasti Academiae Mariscallanae Aberdonensis : selections from the records of the Marischal College and University, MDXCIII-MDCCCLX [1593-1860] by Peter John Anderson and James Fowler Kellas Johnstone, published in 1898 by the New Spalding Club. On page 362 we find an entry and footnote:

1784-88.

Jacobus Cromar,10 f. Roberti de Lumphanan. b, s, t, m, A.M.

10 Under mast., Gram. Sch., 1796; master, 1803.

The Latin, an academic convention of the day, and the abbreviations require some translation. Jacobus (root of the term Jacobite as it happens) is a Latin version of the name James. The letter f. is shorthand for filius, Latin for son of. The name Roberti, of course, is Robert, and de is Latin for of. The strange letters refer to a student’s accomplishments. The letters b, s, t, m refer to the Latin words Bajan, Semi, Tertian, and Magistrand, which identify the four individual years of attendance. The main degree awarded by Marischal College was the A.M. (Artium Magister), a credential for which a student took a four year course of study. In the footnote, it indicates James takes on the position of under-master, and later school-master, for the Grammar School.

Parenthetically I’ll mention in the notes below other Cromars who became alumni of Marischal, but this James is the one of primary interest here, because he can help to identify his father Robert, who it happens is also the father of John 1755. We can claim this as a strong hypothesis because the dates and places are compatible in their birth records: James is born 1765 in Aboyne, ten years after John is born, also in Aboyne. James, a scholar of repute whose death was noted in the 1825 volume of Scots Magazine at age 60, begins to hypothetically tie this family group together fairly nicely.

Finding Jannet Dun or Janet Dunn or Janet Dune

The lines to the wives of these obscured Cromar men always seem to be a bit simpler to tease out. We can pretty easily confirm a Jannet Dun as the wife of Robert Cromar giving birth to Rebeka Cromar in 1752 in Kincardine O’Neil, where Jannet herself was also born. But this gets kind of tangled as we discover no less than three Janet/Jannet Dun/Dune/Dunn personages born in the same town in 1712, 1714, and 1728. The age of Robert, who we presume is born 1717 or later based on scant evidence, suggests the 1714 Janet as closest in age, but the age of youngest son James, born in 1765, tilts heavily in favor of Janet 1728. More research will be needed to pin this down.

Conclusions?

I thought the search for John and Ann Cromar was a rollercoaster, but I was certainly not prepared for the journey to find John’s parents! There are still mysteries here, but I’m reasonably confident in claiming the following working hypothesis:

- John’s parents are Robert Cromar and Jannet Dun.

- Robert is probably born in 1717 or later, probably in Aboyne or environs.

- Jannet is probably born in 1714 or later, probably in Kincardine O’Neil.

- John has several siblings including Rebeka 1752 and James 1765. Birth and various other records suggest the family starts in Kincardine O’Neil, moves to Aboyne, and later ends up in Lumphanan, perhaps even becoming the first Cromar tenant farmers at Milton of Auchlossan.

These conclusions are strictly circumstantial and probable. Unless more research can turn up more primary source evidence, we can’t claim conclusive results. For now this must merely stand as a hypothesis. Is our search to link this family branch to Peter Cromar doomed?

Notes

It turns out that I (a college digital art professor) and my sister Paige Cromar Davis (a high-school science teacher) are continuing a family tradition: we are but two among a long line of school-masters! In Fasti Academiae Mariscallanae Aberdonensis : selections from the records of the Marischal College and University, MDXCIII-MDCCCLX [1593-1860] Anderson, P. J. (Peter John), 1852-1926 (Editor); Johnstone, James Fowler Kellas, 1846-1928 pub 1898 Aberdeen : New Spalding Club, we note the following entries for Cromar uncles and cousins who are alumni:

ALUMNI AND GRADUATES IN ARTS.

1766-70.

Jac. Cromar.16

16 Under mast., Gram. Sch., 1778 ; master, 1781.

1783-87.

Jacobus Cromar, f. Roberti, Lumphanan. b.

1784-88.

Jacobus Cromar,10 f. Roberti de Lumphanan. b, s, t, m, A.M.

10 Under mast., Gram. Sch., 1796; master, 1803.

1787-91.

Geo. Cromar, f. Patricii in par. de Lumphanan, Aberdeen. b, s, t, m, A.M.

1795-99.

Geo. Cromar, f. Roberti in Aboyne, Aberdeen. b, s, t, m, A.M.

1819-23.

Ro. Cromar,3 f. Jacobi, rectoris Scholse Gram, de Aberdeen. b, s, t, m, A.M.

3 Adv. in Aberd., 1829.

1826-30.

Georgius Cromar,8 f. dem. Jacobi, rectoris Gram. Sch., Abredonensis. b, s, t, m, A.M.

8 Hon. dist. ; sch., Forres.

Leave a Reply