Official data is the life-blood of genealogy, and while a careful researcher can infer a lot about family dynamics from documentation, it can only get you so far. Genealogists are right not to place stock in anecdotal evidence, but data is sometimes a skeleton that lacks the flesh only family stories can supply. Perhaps official data points are like the keyframes for an animation in which family stories supply the tweens.

To capture some of our own in-betweens, in late June 2021 I “interviewed” my father, Charles Robb Cromar, Jr. Born in 1937, he’ll be 84 this year. I’m not sure how many people act like journalists to document family stories like the ones we captured in our chat, but a lot of family history is certain to be lost without the effort. My dad is the last living person with eye-witness experience of the life of my paternal great-grandmother, Christiana Robb, and if he were to pass without our chat having happened, all the stories below, and several stories in blog posts to follow, would pass with him. If anyone should be considered a primary source, it’s my dad.

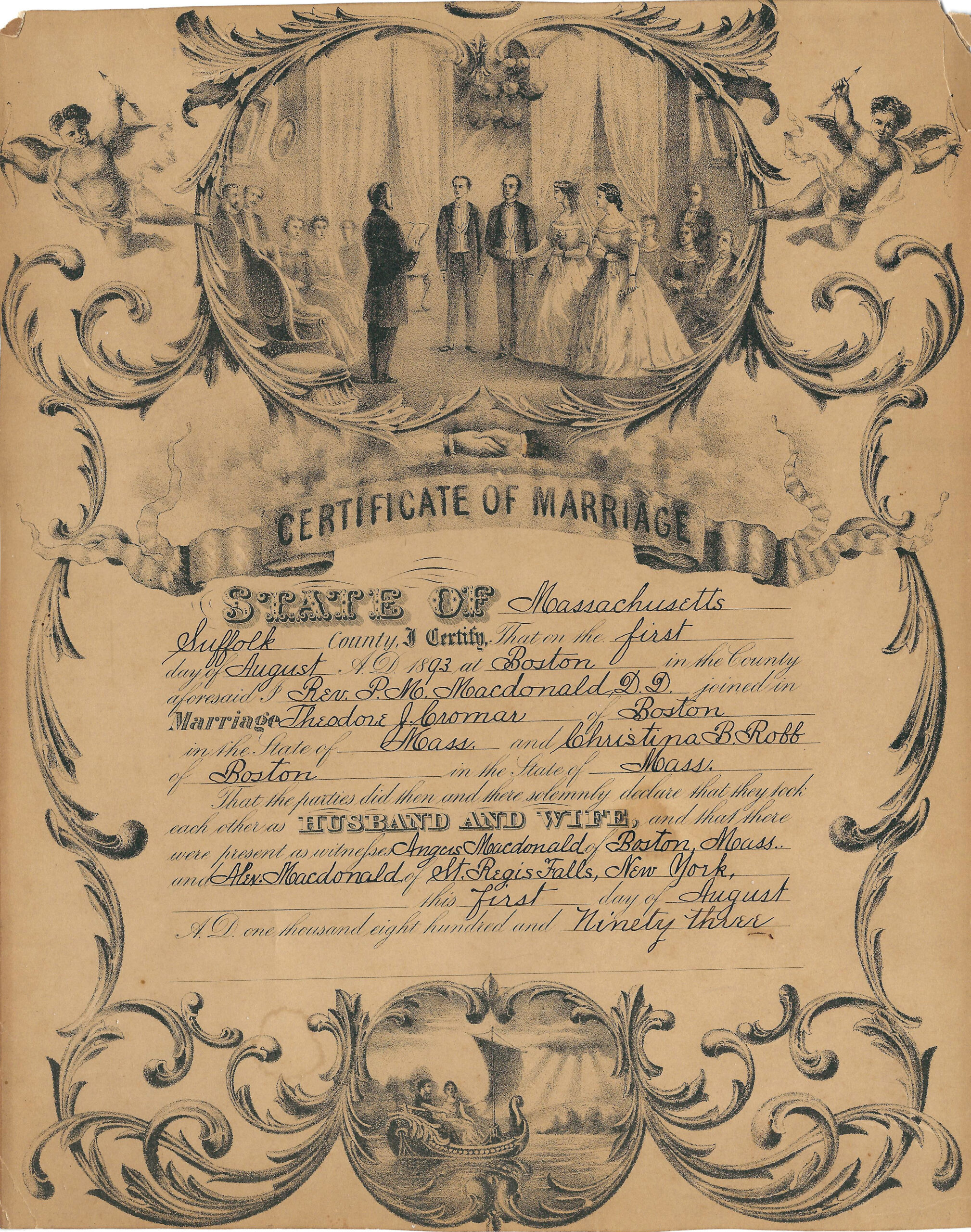

While on my visit with him, we also uncovered a treasure of family memorabilia, including the original copy of Thuddie and Teenie’s certificate of marriage, which I dutifully digitized. It’s an interesting coincidence that the surname of the witnesses is MacDonald, since the family mythology that spurred this blog into being claims that the Cromars derived from MacDonald stock lost to the mists of time.

Marriage certificate, collection of Charles R. Cromar, Jr., digitized by the author

After Broad Street Station

During the 1920s, Thuddie had built a stonemason contractor business of some repute in the region. Though there are no census records to substantiate the family’s residence in the South—only in Annapolis, MD can we find official data—there is a trail of important, well-documented construction projects that trace the Cromar’s movements. If we only follow official data, we assume (as I did in Thuddie and Teenie in the New World) that, from Irving Street in DC around 1913 to the completion of Broad Street Station in 1919, they had some minimal relationship with Richmond, VA, though with no proof of address, and by 1920 were in Annapolis MD. I had characterized the ’20s as fairly sedate for the family. My father’s information proved that I could not have been more wrong! The family was more on the move than ever. Just follow the buildings.

Cromar and Sons was a stonemason contracting enterprise that included the founder Theodore and employed sons Teddy and Charles. It appears that just as Thuddie had apprenticed to family back in Aberdeenshire, the stonemasonry tradition was being passed on to a new generation of New World Granite Men. After Thuddie’s work at Broad Street Station in 1919, their services were very much in demand during the building boom of the Twenties. In 1928, when the family started a whirlwind of activity, Teddy was 28 and Charles was 21. There was so much work on their plate in 1929 it’s clear that Thuddie’s role was as at least as much on the administrative side as it may have been in the trenches.

Art Deco Innovations

In the late 1920s, the family specialized in the construction of large-scale, award-winning projects in the Art Deco style, a relative rarity in the South. These were tall, civic-minded, urban and urbane constructions that included the Central National Bank Building in Richmond, VA; the R. J. Reynolds Building in Winston-Salem, NC; and the Hotel John Marshall and Thomas Jefferson High School, both in Richmond. All four of these structures are on the National Register of Historic Places, sharing that honor with Broad Street Station.

Central National Bank

A 23-story Art Deco skyscraper at the corner of 3rd and Broad Streets, designed by John Eberson of New York with Carneal, Johnston, and Wright serving as local architects. Doyle and Russell, who later worked on the Pentagon in Washington, were the general contractors who the Cromars were subcontracted to. According to a detailed history at RVA Hub, CNB was founded by Richmond merchants in 1911, and by the late 1920s its directors voted to create a new headquarters building. Construction started 1928, completed in June 1930. This timeframe suggests the exterior envelope was completed well prior to October 1929, since the building trail and timeline indicates Thuddie and sons had moved on to other work.

1 | Contemporary new construction view of the Central National Bank of Richmond.

2 | A modern view from the side.

3 | The renovated interior.

4 | A vintage shot of the same.

R. J. Reynolds Building

A 21-story Art Deco skyscraper at 4th and Main Streets in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, designed by Shreve and Lamb, the same architects who designed the Empire State Building for which this building is a clear precedent—legend has it the staff of the Empire State sends a Father’s Day card to the staff at the Reynolds tower annually! James Baird and Company provided general contracting services. The Reynolds building and plans are nearly identical to the CNB. During the time of construction, the family lived in Winston-Salem.

1 | A comparison shot of Shreve and Lamb’s father and son: Reynolds Building and Empire State Building.

2 | Modern aerial view of the Art Deco setbacks on the Reynolds.

3 | Modern interior hallway view.

4 | Modern lobby view, restored to Art Deco glory.

5 | A 1934 postcard, essentially a contemporary image for the new construction. | Wikipedia Public Domain

6 | Stonework cladding the steel frame: this was fast construction work, which may explain how the Cromars could do so many projects in such a short span of time. Note also the watermark at lower right naming the architect and general contractor.

Hotel John Marshall

Fourteen stories of eclectic opulence, the Hotel at Fifth Street between Franklin and Grace was designed by Marcellus E. Wright, with Wise Granite and Construction Company serving as general contractors overseeing the Cromar’s craftsmanship. It opened, ominously, on the day after the stock market crash: 30 October 1929.

1 | 1957 view of the Hotel John Marshall.

2 | The invitation to the gala opening, the day after the Great Crash.

3 | Modern photograph of the renovated grand stair. The hotel is now private residences.

Thomas Jefferson High School

Constructed 1929-30. The architect of this school was Charles M. Robinson. Constructed in 1929-30, my father roamed the halls built by his grandfather and graduated from TeeJay in 1957.

1 | 1950 photograph of the entry of Thomas Jefferson High School. Note the sculptural flourishes, including sphinx-like portraiture and the Art Deco style eagle atop the sphere at the apex of the ziggurat topping out the entry tower.

2 | A postcard rendering, also displaying the eagle. | Digital Commonwealth

3 | A modern photograph, revealing the mounting post atop the sphere, with the eagle now missing. | Via Flickr, CC-BY-SA

The late Twenties had been a successful era for Cromar and Sons, and there was a lot to celebrate as the family raised a triumphant Art Deco American Eagle sculpture to the pinnacle of the school’s ziggurat tower by crane. But the eagle is now no longer present: the NRHP application for the building notes that at some point this eagle sculpture vanished. Today, one can observe the mounting post emerging from the sphere that remains. Though the report doesn’t say how it disappeared, a common reason for removal of high-flying ornamentation like this is damage by a lighting strike.

While we don’t know the cause, we do know that the stock market’s Great Crash, a cataclysm occurring at the exact same moment the Cromars were hoisting their ill-fated eagle on 29 October 1929, hit the construction trades like a bolt. Firms like Cromar and Sons disappeared with the onset of the Great Depression.

Hard times

And that was the end of Cromar and Sons. Within five months of the crash, Theodore was dead. There is no record of the cause, and that taboo phrase — death by suicide — has never once been suggested in family lore. Of course, we do well not to forget Theodore’s father John and his untimely death at age 47 due to the occupational hazards of silicate dust, so it’s quite plausible Theodore himself succumbed to a vocationally related disease.

While the record does not pinpoint cause of death, we can certainly say that, for a prideful 61-year-old man whose living was made by a balance of raw muscle and fine dexterity, staring at the abyss of the Depression with the keen eye of a consummate craftsman provided little cause for optimism. Whatever will there was to live seemed to be sapped by forces of history too strong for even a Granite Man to overcome.

Death record file card, screen-capture from Maryland State Archives.

The aftermath

The loss of the family’s strong paternal anchor combined with the evaporation of a secure future in a trade was obviously devastating to Teddy and Charles. Teddy had married Mary Wilson in 1922 in Petersburg, and they had borne a son in 1926, Theodore III, who later went on to a career as an architect. After Thuddie’s death, they had a daughter, Joan, born in 1932 in Washington, but Teddy suffered another loss with Mary’s early death in 1934. The stress of all this tragedy no doubt took its toll on Teddy, who, like Thuddie, died in his early 60s. It may have been a blessing that he did not live long enough to endure yet another tragedy in the untimely death of Theodore III, at age 45 in 1971. It seemed as if some inexplicable curse had befallen the Cromar men on this branch of the family tree.

Younger brother Charles, meanwhile, managed to find unfulfilling work at Miller and Rhodes department store, but between the instability of the economy and the lifting of Prohibition he had a hard time holding down a job. We’ll explore his struggles in another post.

Life after Thuddie

As she became more dependent on assistance for living, Teenie would shuttle between the families of Teddie, Ann, Marion, and Charles, spending about 3 months with each of them in turn. This shared caregiving may explain how it came to be that Teenie died in Montgomery County, Maryland and not Annapolis, which still appears at that time to be some kind of official correspondence address for her. When she stayed with Charles and his family at 3156A Floyd Avenue, the population for their two-bedroom flat defies belief: Charles and his wife, Helen; my dad, and his older sister Robbie; Jimmy Hawkins, Helen’s nephew, and Helen’s brother, George. Teenie was not the only grandmother who would temporarily inflate the population, either. Grandma Hawkins would shuttle between families as well, so this seemed to be a common practice in these times.

The house at 3156A Floyd Avenue, a twinnish-looking affair, but with access to the top floor flat via one of the two doors. | Screen-captures from Google Map Street View

Tight quarters

So, whenever a grandmother was in the house, which seems to be at least six months out of the year, there were 7 people living in a 2 bedroom second floor flat right around the corner from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and the shopping district of Cary Street, where my dad and his crew would commit the innocent acts of mayhem common among idle young boys in the city. This was the house where my dad heard tales, offered in a soft Doric lilt, of long-lost MacDonald brothers changing their identities and evading persecution—and, so far at least, this family history as well.

My dad’s childhood appears not to have been a particularly easygoing one in this crowded house. The family had suffered through the Great Depression and was of course enduring World War II. Charles Sr. had turned to alcohol to self-medicate, and would often come home intoxicated. Somewhat of a mean drunk, he would announce his arrival from the bar by making rough sport with the furniture, although my dad made it crystal clear that his father never brought his temper to bear directly on his wife or kids. He may simply have terrorized them, and probably the neighbors in the flat below, tossing plates around and breaking stuff, but he never crossed the line into physical abuse.

Teenie’s passing

By the time Teenie passed away, my father had married Janice Cleaton and had recently returned from a stint serving in the Air Force as a Cold War radio coder; he can still tap Morse Code without missing a beat. I was born just over a year before Teenie died on Christmas Day 1960, and it’s likely she got to see her new great-grandson a few times, but the amnesia of infancy robs me of any recollection of that experience. Transcribing my father’s memories in this blog post is the best I can offer posterity.

New World timeline

Since these dates are spread over three posts, I’m synopsizing the major events of Thuddie and Teenie’s new world experience below.

| Year | Place | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1891 | ME, MA, NH, VT | Theodore emigrates Itinerant stonemason |

| 1893 | Boston, MA | Christiana emigrates Marriage Itinerant stonemason |

| 1895 | 22 Smith St Boston, MA | Birth of Anne Christine |

| 1897 | 22 Smith St Boston, MA | Birth of Marion Robb |

| 1899 | Boston, MA | Mother Ann George emigrates |

| 1900 | 22 Smith St Boston, MA | Theodore naturalized |

| 1900 | 22 Smith St Boston, MA | Birth of Theodore Robb |

| 1907 | 15 Warner St Boston, MA | Birth of Charles Robb |

| 1910 | 230 Millet St (acutal: ~60 Millet St) Boston, MA | Census record |

| 1910 | 171 State St Augusta, ME | Stonemason, State Capitol |

| 1913 | 527 Irving St Washington, DC | Stone Contractor, work undocumented Ann George dies |

| 1917 | Richmond, VA | Stone contractor, Broad Street Station |

| 1920 | 181 West St Annapolis, MD | Stone Contractor, work undocumented Christiana visits Scotland Feb-Jul |

| 1928 | Richmond, VA | Stone Contractor, Central National Bank Building |

| 1929 | Winston-Salem, NC | Stone Contractor, R J Reynolds Building |

| 1929 | Richmond, VA | Stone Contractor, Hotel John Marshall Stone contractor, Thomas Jefferson High School |

| 1930 | Anne Arundel County, MD | Theodore dies |

| 1930 1960 | MD, DC, VA | Christiana lives with children |

| 1960 | Montgomery County, MD | Christiana dies |

Leave a Reply